The Comstock House is a private family home in Santa Rosa, California. It is currently undergoing a restoration intended to return the exterior to its original 1905 appearance. The house is named for the Comstock family, who lived here for 74 years.

Comstock House would be noteworthy if only for its link to the illustrious family, but it is a remarkable example of early 20th Century architecture that remains in mostly original condition. The main rooms of the house were never remodeled, and still appear almost exactly as they did in 1905. Also rare is that the original blueprints and the architect's directions to the contractor have been preserved (both documents available for download from this web site). In 2012, Comstock House was listed on National Register of Historic Places (NRIS 11001053).

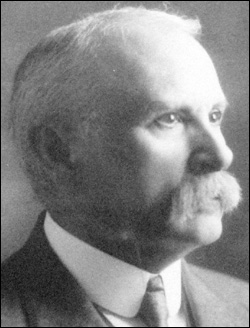

BRAINERD JONES (1869-1945)

The architect for Comstock House was Brainerd Jones, who created more than a hundred homes and office buildings in Petaluma, including most of the town's historic core. In Santa Rosa he designed only seven known homes, five of them still existing, including the nearby Belvedere/Lumsden House which is also listed on the National Historic Register (NRIS 83001245).

Jones was versatile in designing houses to suit his clients. Other homes in Santa Rosa reflect his electic skills, representing Prairie Style, Colonial Revival, and American Queen Anne, all popular designs in the early 20th century. For Comstock House he instead reached back 25 years to the East Coast Shingle Style, which included an open floor plan, an astonishing number of windows, and featured the use of shingles to give the home a rustic, "natural" look. In his directions to the contractor Jones even embraced the radical ideals of architect Wills Polk and specified no paint was to be used inside or out; architecture, in this view, was no different than fine, artisan furniture.

Brainerd Jones included an unusual number of whimsical features in this design. Almost everything appears off-center; left/right, front/back views of the house are never symmetrical. The right sides of the gambrel gables are uncompleted (but on the east and south side only) and on south end of the porch is a decorative giant corbel that appears to be supporting the top floors. The attic windows at the front of the house cap a very deconstructed Palladian motive, above bay windows that are really more of a bulge than bay.

|

| The Paxton House, demolished in 1969 |

But why Shingle Style? It's likely because just two doors down, the owner's good friend Blitz Paxton had Jones design a Shingle Style house that was built there in 1902. Jones now had the rare opportunity to expand on his earlier theme as well as unifying it with the new house.

Together, the two houses must have made quite a statement; although the Paxton home was wider, they were on the same scale and the same distance from the street. There were no other shingle style houses in this neighborhood, and maybe nowhere else in Santa Rosa. Alas, we know little about Paxton House interiors. We know from newspaper accounts that there was a reception hall and it followed basic East Coast Shingle Style design, so Jones might well have used all natural wood inside that house first. It certainly must have been magnificent; 300 guests attended one party.

|

James Wyatt Oates

(Image courtesy Sonoma County Library)

|

JAMES WYATT OATES (1850-1915)

The home that would be best known as Comstock House was built for James Wyatt Oates and his wife, Mattie. Over his prior quarter-century in Santa Rosa, Oates had forged a reputation as a respected lawyer, a savvy speculator who owned property all over town, and an unerring supporter of his wife's social work. Apparently no one in Santa Rosa knew that he was also a murderer.

Wyatt was the baby brother of William C. Oates, a seven-term Congressman and a one-term governor of Alabama. William most famously commanded the 15th Alabama regiment at Gettysburg that lost the Battle of Little Round Top, often mentioned by historians as a pivotal moment in the Confederacy's defeat. After becoming a lawyer after the war, William defended his brother on charges that Wyatt had murdered a man in a fit of anger. According to William's biographer, Wyatt was only acquitted because his brother bribed the prosecutor - who happened to be the father of the victim.

James Wyatt Oates studied law with his brother's guidance and they briefly became partners before Wyatt moved west. They maintained close ties, William or his family alone traveling to California for lengthy visits at his brother's home. Wyatt and Mattie did not have children but had long mentoring relationships with at least two young women, and in the last years of his life, Wyatt would also follow his brother's example by helping a young man named Hilliard Comstock privately study for the bar.

Wyatt's writings reveal he had deep sentimental feelings about the Old South, so it is somewhat surprising that he did not direct architect Brainerd Jones to design a home in ante-bellum Alabama plantation style. Instead, Oates appeared to give Jones a free hand; in the local newspapers he was quoted as boasting "nothing that money and taste can provide will be omitted in making it a comfortable and attractive home." Jones now had a good budget and someone not too particular about the particulars.

Sadly, the Oates family had a short tenure at their grand home. Mattie spent most of her years here as a semi-invalid before dying in 1914. Wyatt deeply mourned her passing until he died the next year from pneumonia, following a visit to the young woman whom he and Mattie appeared to regard as something of a daughter. Despite his long experience as an estate lawyer, their beloved house was left to sell in probate. The remains of Wyatt, Mattie, and her mother were cremated together.

|

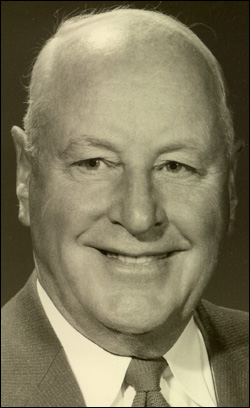

Hilliard Comstock

(Image courtesy Martha Comstock Keegan)

|

CORNELIA "NELLIE" COMSTOCK (1857-1940)

The year after Oates died, the home was purchased for $10,000 by Nellie Comstock, the mother of Oates' young legal protegee, Hilliard Comstock. Nellie was the daughter of Harvey B. Hurd, a lawyer best known for revising and rewriting the entire statute law for the state of Illinois after the Civil War. A civic leader in Chicago, he was credited with legislation that finally resolved the city's historic water and sewage problems and was also an early advocate of a separate justice system for Chicago's children. Hurd had an historic role as an abolitionist. As secretary of the National Kansas Committee providing funding and material support for John Brown, it was Hurd who made the consequential decision in 1857 to provide Brown's colony with planting seed and clothing, but not guns. Brown later met with the committee in Chicago and they were shocked at his poor appearance, with his clothes in tatters. Since Hurd was about the same size as Brown, a suit was made to his dimensions and given to John Brown. Years later, Hurd would quip he was glad not to still be in those clothes when the wearer was hanged.

An artist and writer, Nellie educated all seven children herself with the aid of private tutors. Many went on to careers in the arts and sciences. Oldest son John Adams Comstock Jr. became one of the world's leading experts on butterflies and later the Associate Director of the Los Angeles Museum. Earlier he and sister Catherine were in charge of Elbert Hubbard's Roycroft shop in East Aurora, New York, which spearheaded the American Arts & Crafts movement. John and Catherine moved to Santa Rosa in 1908 and opened a retail store and art gallery in downtown Santa Rosa, where they sold their leathercraft alongside the work of the most respected artisans in the movement. Later Catherine and her husband were founding members of the Carmel-By-The-Sea art colony in the 1920s and joining her in Carmel was youngest brother Hugh, who became a self-taught architect and builder known for the whimsical "fairy tale" cottages that are still a hallmark of the community.

HILLIARD COMSTOCK (1891-1967)

When Nellie died in 1940, her home passed to son Hillard and his wife Helen (see biography page), who would become the most well-known residents of Comstock House. A Superior Court Judge for 35 years, Hilliard did not have a law degree, but studied under Oates' guidance before passing the bar and becoming a partner in 1912. He took over the practice after Oates' death, but not before serving in the National Guard infantry and U.S. Army, where he rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel after commanding troops in the 1918 Second Battle of the Somme in WWI.

Like his grandfather, Hilliard became a key civic leader with a keen interest in children's issues. He was president of the Santa Rosa Board of Education from 1920-1929, a period of reorganization and rapid expansion that included construction of Santa Rosa High School, four elementary schools, and launching the building program for the junior college. Hilliard was best known as a Superior Court judge for 35 years, always re-elected without opposition. In that time his decisions were reversed only seven times by the Appellate Court, and when those reversals were appealed to the California Supreme Court, all but one of them reverted back to Comstock's original decision. Hilliard was a leader in the creation of Howarth Park and the drive to build Memorial Hospital, and president of the NRA 1942, 1943. The downtown city transit mall and a pedestrian corridor are named in his honor, as is a middle school not far from Comstock House.