|

|

BEHIND THE DESIGN

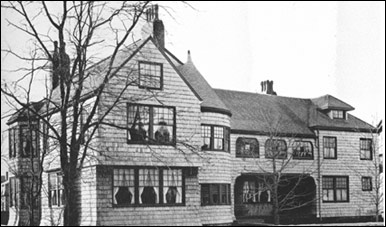

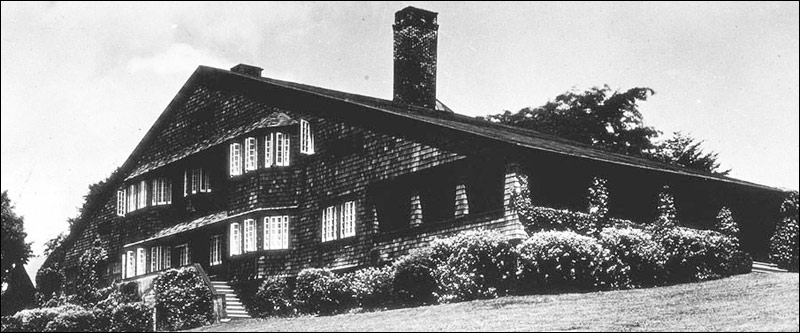

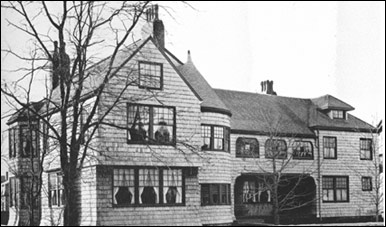

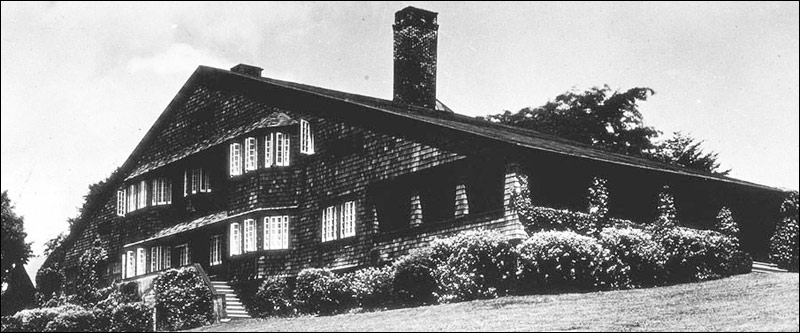

Architectural elements of Comstock House: East Coast Shingle Style

"Attorney James W. Oates has let the contract for the handsome residence he will erect at Healdsburg avenue and Benton streets ... It will be built colonial style, and will be arranged very picturesquely"

- Santa Rosa Press Democrat, August 26, 1904

|

ARCHITECTURAL REVIVAL

The general style of Comstock House is "Dutch Colonial Revival," with its steep, two-angle gambrel roof. This design was often used in colonial America because it had an advantage over a simple pitched roof, which often needed load-bearing inside walls or braces to hold the weight. The gambrel's truss design instead shifted the weight to the outside frame. The top floor could now be used

as a single open space (hence the gambrel's popularity in barns with haylofts), or sectioned up into rooms in any arrangement desired. The nearly vertical angle of the roof also meant that nearly all that inside space was usable, while as much as a third of the interior under a pitched roof was too low to use. The steepness also eliminated worry about snow and ice buildup, and while rain gutters and downspouts were almost unknown in America until the 18th century, the bottom of a gambrel roof often ended in a curvy "kick" overhang to shoot rainwater farther away from the walls and foundation. 1

The general style of Comstock House is "Dutch Colonial Revival," with its steep, two-angle gambrel roof. This design was often used in colonial America because it had an advantage over a simple pitched roof, which often needed load-bearing inside walls or braces to hold the weight. The gambrel's truss design instead shifted the weight to the outside frame. The top floor could now be used

as a single open space (hence the gambrel's popularity in barns with haylofts), or sectioned up into rooms in any arrangement desired. The nearly vertical angle of the roof also meant that nearly all that inside space was usable, while as much as a third of the interior under a pitched roof was too low to use. The steepness also eliminated worry about snow and ice buildup, and while rain gutters and downspouts were almost unknown in America until the 18th century, the bottom of a gambrel roof often ended in a curvy "kick" overhang to shoot rainwater farther away from the walls and foundation. 1

If the gambrel's superior design didn't convince the neighbors to rebuild, the controversial Federal Direct Tax of 1798 probably won converts to the Dutch roof. America's new Congress authorized a one-time tax on slaves and other property, and assessors counted windows to help determine property value. Although gambrel roof houses had two, sometimes three stories of living space, the roof doubled as the wall for the upper floor(s), with dormer windows bringing in light on the sides. Thus according to the "Window Tax" guidelines, they were sometimes classified as single-story homes, and taxed at a much cheaper rate.

(MORE)

|

|

|

Any resemblance is probably coincidental

|

(There's actually nothing particularly "Dutch" about the style -- gambrel roofs were used in many countries since medieval times. Homes of this type in America were most common around the Hudson River Valley and northern New Jersey, where many colonists came from Holland. It was also said that the roof profile, with its flair on the bottom, resembled a traditional Dutch cap, which it does, in a way.)

The gambrel design found renewed popularity starting in the 1870s because of a paradox: It suited the tastes of both those who wanted an older "colonial" look as well as the new breed of upstart American architects who were designing modern, even futuristic, homes.

As the 1876 centennial approached, a wave of nostalgia swept the country for the first time. Probably driven in part by escapism from hardships of

the ongoing Long Depression,

popular books and magazines glorified America's colonial past with sentimental tales of Revolutionary days of yore, illustrated with drawings of cozy cottages and Elysian farms, where everyone supposedly lived and worked in harmony and fought the heroic cause (the bloody and divisive Civil War had also ended just a few years before, remember). All things colonial became fashionable again, particularly furniture and building styles. It's important to understand that their meaning of "Colonial Revival" architecture was far different from ours today. Where we now match colonial revival buildings against fairly rigid checklists that dictate how elements of each style are "supposed" to appear, in the late 19th century colonial meant simply, "old and picturesque;" if pressed, someone might have pointed to a Dutch, Georgian, or Puritan-era house as an example.2

Amid this new respect for things old, the "Queen Anne" style emerged, which originated in a parallel 18th century revival taking place in Britain. Architects there were moving away from the heavy gothic style and looking back to their own picturesque historical buildings, including half-timbering that made it look as if the framing of the house were partially exposed. Queen Anne style was widely seen for the first time in America at the 1876 Centennial Exposition, with the British government buildings built in that manner. So strong was the sehnsucht for the past that the most talked about buildings weren't the ones built in the modern style (check out the beautiful Stick Style offerings from New Jersey and Michigan state exhibits), but the Tudor reinventions at the British compound. Fairgoers also packed a replica New England Kitchen of 1776, where they could interact with players in colonial costumes.

|

|

How to hide a box: William M. Woollett's 1878 book of house plans,

"Old Homes Made New" showed how to mask the box-like shape by turning it into a Queen Anne, with loads of other Victorian filigree

|

For Victorian era architects, the new Queen Anne and old Dutch styles shared a central appeal: They weren't boxes. Earlier the United States had been mired in the conformity of a Greek Revival period, and most Early American homes, grand and simple, were dominantly a simple square or rectangular block. Thomas Jefferson reinforced this squareness during his presidency by promoting classical designs, with rigid mathematical

symmetry and proportion as ideals. Builder's guides and manuals often didn't even contain house plans, but only directions on how to best build according to classical principles and apply classical decorations.

But starting in the mid-19th century, the trend was to conceal or distract from boxy shapes. The trend exploded with the Queen Anne style, which hid the underlying right angles of the structure became hidden behind elaborate porches and verandas, gables, overhangs, witch-hat turrets, not to mention myriad decorative features.

The limits of this add-on school of construction were reached before the end of the century; no matter how ornate the final appearance, builders were ultimately only tacking more boxes (and cylinders, cones, and other basic geometic whatnot) on the sides of the same basic house-box. The Dutch roof with its odd angles gave it the starting advantage of being the least cubical shape around. Thus while builders continued to use the design for homes in the retro colonial revival spirit, architects from the 1870s onwards increasingly relied upon the gambrel shape and other kinds of roof-walls in their quest to create something modern.

|

A NEW, OLD STYLE

|

Richardson's 1875-76 William Watts Sherman House

(CLICK for photos)

|

If the profile of Comstock House is Dutch Colonial, its character lies within its shingled skin.

Besides the Tudor-inspired British compound at the Centennial Exhibition, many commented on the Japanese buildings. Here was shown an architectural esthetic with simple, clean lines and the highest craftsmanship; an observer said it was "as nicely put together as a piece of cabinet work." 3

Inside was an open floor plan without doors or even permanent interior walls, and the exterior was covered in plain shingles, the sides uncluttered with the stickwork and endless ornamental frill that was considered de rigueur for nice American homes at the time.

These Japanese principles were in synch with homes starting to be designed by a new generation of architects in England and America. Partly in rebellion against the classical Roman/Greek architectural ideals of perfection taught at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris, these founders of the Queen Anne style had an appreciation for the less-is-more quality of "negative space" found in Japanese design. In the ongoing debate over whether architecture was more than functional design, they came down strongly on the side that architecture was Art, just as much as painting or sculpture.

Queen Anne, then, had two mothers in the 1870s: The nostalgia-driven love of homes picturesque, and the artistic drive by professional architects to create something original. Almost immediately the two interests also began to diverge. As the decade ended, popular home designs continued to emphasize the neo-Tudor look, and would soon mash together every storybook element imaginable.

Many architects were taking another path, already starting to phase out half-timbering and other faux historical features and simplifying designs into what would later be dubbed, "Shingle Style."

More than any other building, an English manor-style house designed by Henry Hobson Richardson defined Shingle Style and pointed towards the future of American architecture. His 1875 Watts Sherman House had tall chimneys that presented strong vertical lines in the Stick manner, but the design emphasis was more on width than height. Overhangs stretched the great roof even further outward, and banks of windows turned walls into glass, features that would become hallmarks of Frank Lloyd Wright designs decades later. Like the British-style Queen Anne homes, visitors stepped inside to a grand, open "living hall" that was the ancestor of Wright's "Great Room." But what many noticed most was Richardson's use of the humblest material on his masterpiece house: wood shingles.

|

Alexander F. Oakey's 1877 Dorr House

(CLICK for more detail)

|

Shingle siding was hardly new. Since colonial days, shingles had been used in damp, coastal Rhode Island, which was where the Watts Sherman House was built. Richardson had used them on other projects in recent years, as had colleagues. But Richardson and others were using shingles ornamentally, in place of the hard-to-manufacture terracotta tiles used for English Queen Anne wall decoration -- and, not inconsequentially, they were using these cheap shingles on expensive country homes. Artistically, a building wearing a coat of wood shingles had completely the opposite look from the skeletal Stick Style, then at the zenith of its popularity.

Rarely has an architectual idea caught on so fast; in the following few years, shingles were widely accepted as a signature element of the modern style.

Shingles made cylindrical turrets and other curvy features of a Queen Anne easy to build, and unlike England, wood in the United States for the shingles was cheap and plentiful (although these early shingles were often pine or cypress, not cedar).

Also important to this revolution in architecture was coverage in a variety of magazines, particularly American Architect, Building News and Harper's Monthly.

Vincent J. Scully, the authority on this history, makes the interesting observation that printing technology may have played a key role in the development of architecture at the time; as engraved illustrations favored the sharp lines of the Stick Style, the Shingle Style took off in the 1870s at the same time as improvements in lithography made it easy and affordable to reproduce photographs, which favored the softer contours of shingled walls. 4

In these pages, theories and aesthetics were hotly debated and the latest designs shared. Harper's published a series of influential articles on the Queen Anne style (and where the author pleaded with fellow architects to adopt "good old types of Dutch and Puritan architecture" as the "official" American revival style5). But the best reading was usually in the letters section, where architects squabbled no end, defending and attacking, sometimes anonymously. If the architect of the 1870s wasn't an artist, he certainly argued like one.

As Scully noted in his book, "This was a self-conscious generation, tormented, as the men of the mid-century had seldom been, by a sense of history, of memory, and of cultural loss. Vaguely disturbed by the materialism of American culture as they found it, conscious of a spiritual mission to improve it, at the same time proud of themselves as a professional class."6)

For these young Turks, architecture wasn't limited to building design. Alexander F. Oakey, who designed many remarkable homes, was probably best known in his day for his writings on interior decoration, and particularly his 1881 book on landscaping, "Home Grounds." Pioneer landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Central Park and hundreds of other public parks and academic campuses, created grand settings to compliment the grand homes of top architects such as Richardson and the firm of McKim, Mead, and White.

The 1881 McCormick House showed how quickly the style evolved. It shared the basic elements of Richardson's house -- width, windows, tall chimneys, tall roof -- but was completely shingled. The exterior was purged of revival ornamentation, decorated instead with fine latticework that suggested Asian wicker or rattan, along with two oval plaster panels inset with glass and seashells that must have glimmered brightly in the sun.

|

|

McCormick House, "Clayton Lodge" built in 1881-1882 by the architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White. The house was demolished in 1957 - CLICK for for a later view

PHOTO: Wisconsin Historical Society

| |

|

|

Stoughton House, designed by Richardson in 1882. Few online photos are available, in part because it's now hidden behind mature trees and a high fence. An assortment of images are available

here.

PHOTO: Sheldon's Artistic Country Seats

|

|

|

|

An 1890 American Queen Anne by George F. Barber, whose formulaic designs came to define the style

|

Eight years after designing the Sherman House, Richardson again broke new ground with the Stoughton House in Cambridge, Massachussetts.

With plain shingles, the home was devoid of ornamentation, all lines strongly marked; it could as easily been built with rough-hewn stone instead of wood. Architects of the day were startled; no modern house looked so...naturalistic. Even the original shingles were painted olive-green and lacked the bright colors of freshly milled wood. Richardson had trumped the revival fad of building houses in the old manner -- he had created a new building that really looked like it had been there for a century or three.

While they were greatly different in outward appearance, the 1875 and 1882 Richardson houses shared the same concepts: a broad profile; an astonishing amount of window space; and open interiors, which transformed hallways and vestibules from mere circulation corridors into living spaces. These were signature elements in all of the great Shingle Style homes.

The Stoughton House was also notable for what it lacked: whimsy, which had become the signature element of Queen Anne design. The years of 1883-1884 turned out to be bellwether in the split between Shingle Style architecture and "American Queen Anne" style. A Queen Anne exterior was brightly painted, if only in white; a shingled house had the muted shades of sawn wood. You can easily chart out a list of numerous opposites: stylistic vs natural, busy vs simple, exuberant vs restrained, rigidly geometric vs continuous, flowing surfaces. One could be designed only with a draftsman's sharp pen; the other, almost sketched in charcoal. Shingle Style and Queen Anne shared curves, but with the latter it was mostly ornamental flair (see: whimsy) that could have been included or not. One looked like it had been finely constructed from parts; the other look like it could have grown from the earth, or was sculpted from living wood. No judgement here: There was nothing inferior about either. They were just divergent branches from the same root.

The first of a rash of Queen Anne pattern books appeared at this time, such as Shoppell's "Modern Low-Cost Houses."7

Whether by cause or effect, Queen Anne innovation also stopped; from then on, Queen Anne features would join Stick Style in the grab bag of decorative tricks to hide the box.

It's not the purpose here to burrow deeply into the evolution of the Shingle Style -- although there's currently no Internet resource that offers that, sadly -- but tributes must be paid to what other architects created in those years. Some imitated Richardson or the landmark firm of McKim, Mead, and White, but others stretched the limits of design to advance their art. Many of these marvels are now demolished, which makes American Country Houses of the Gilded Age a particularly valuable resource, presenting excellent period photographs and contemporary comment.

Of the classic Shingle Style homes that still exist, many have been altered beyond recognition; rare is the 1884 Loring House built by William Ralph Emerson, which has been restored to its glory, complete with gardens

(slideshow).

But one remarkable house built in those early years must be singled out for honor: The 1887 W.G. Low House, which looks modern even today.

|

|

W.G. Low House by McKim, Mead, and White, 1886-1887. The house was demolished in 1962 so the owner could build a ranch house.

|

No other architectural style in American history developed so rapidly and radically; it's hard to believe that only a dozen years passed between the neo-Tudor Sherman House and the aerodynamic home built for W.G. Low. But as quickly as Shingle Style emerged, it faded even faster. Although a few very nice "free style" homes were built after the Low House, the party was over.

Why did the Shingle Style hit a dead end? It didn't really, of course; Shingle Style was mostly absorbed into the eclectic vernacular of the American Queen Anne. The designs of Richardson and others also were the baseline for 20th century Prairie Style and "craftsman" architecture. A circa 1907 brochure for Cabot's shingle stains (available here as a PDF, but caution -- it's 29M) showcases a hundred homes, most of them clearly descendants of Richardson and crew.

The humble shingle came to represent something more than a construction material; it became a symbol for architects making a uniquely American statement.

But in the opulent "Gilded Age," the rustic look lost favor and classicism again became popular. While the 1876 World's Fair led to the love of homes picturesque, the 1893 World's Fair renewed interest in Greek and Roman formal designs leading to a strong revival of Georgian Style, and architects were tired of the endless arguments over one style being "better" than another. The consensus became that any design was agreeable as long as it had "unity."8

Many of the famous Shingle Style homes also had a fundamental problem because they were "cottages" for the wealthy and intended only for summer use. Those magnificent banks of windows that invited in refreshing breezes threatened a thousand drafts during winter, and that centerpiece living hall risked becoming a frigid cave. By contrast, boxy neo-classical homes could be toasty in the coldest winter, thanks to fewer, smaller windows and claustrophobic floor plans.

Although other Victorian designs were avoided, a family of the 1890s that was heart-set on a home that looked "original" could turn to the Shingle Style's prettier cousin, the American Queen Anne, then at the peak of popularity. Thanks to the pattern books by Barber9 and others, Queen Annes were also easy to build without hiring an architect, and if the client asked the contractor for a house that looked a little different from others in town, another bay window or whimsical turret could always be squeezed in somewhere. And often was.

But the real truth is that Shingle Style innovation didn't fade at all -- it just shifted west, where a new generation of architects launched a renaissance.

|

1

The Architecture of Colonial America (Eberlein, Harold Donaldson; Little, Brown, and

company, 1915), pg 27. The chapter on 17th and 18th century colonial Dutch houses covers the subject in good detail, and also contains photographs not found elsewhere

2

The Shingle Style and the Stick Style: Architectural Theory and Design from Downing to the Origins of Wright, revised edition (Scully Jr, Vincent J.; Yale University Press, 1971). Scully also defined the Stick Style as a unique design

3

American Architecture, 1607-1976 (Whiffen, Marcus and Koeper, Frederick; MIT 1981) pg 294. A two volume set is also available and often easier to find used

4 Scully, pg 10

5 Scully, pg 46

6 Scully, pg 4

7

Building an American Identity: Pattern Book Homes and Communities

(Smein, Linda E.; AltaMira Press 1999); pg. 266

8

On the Edge of the World: Four Architects in San Francisco at the Turn of the Century (Longstreth, Richard; University of California Press 1998) pg 13

9 Untrained as an architect, George F. Barber was virtually a Johnny Appleseed of American Queen Anne Style and other late Victorian era architecture, said to have sold 20,000 house plans nationwide between 1890 and 1908 -- yet despite his influence in defining the popular idea of what a Queen Anne is "supposed" to look like, he's rarely even mentioned. Dover publishes two books of Barber's designs, and one of his later pattern books, "Modern Dwellings" (1901) is available for full download. A note of trivia: The exteriors of the fraternity house in "Animal House" was a Barber home that stood in Eugene, Oregon.

|

The general style of Comstock House is "Dutch Colonial Revival," with its steep, two-angle gambrel roof. This design was often used in colonial America because it had an advantage over a simple pitched roof, which often needed load-bearing inside walls or braces to hold the weight. The gambrel's truss design instead shifted the weight to the outside frame. The top floor could now be used

as a single open space (hence the gambrel's popularity in barns with haylofts), or sectioned up into rooms in any arrangement desired. The nearly vertical angle of the roof also meant that nearly all that inside space was usable, while as much as a third of the interior under a pitched roof was too low to use. The steepness also eliminated worry about snow and ice buildup, and while rain gutters and downspouts were almost unknown in America until the 18th century, the bottom of a gambrel roof often ended in a curvy "kick" overhang to shoot rainwater farther away from the walls and foundation. 1

The general style of Comstock House is "Dutch Colonial Revival," with its steep, two-angle gambrel roof. This design was often used in colonial America because it had an advantage over a simple pitched roof, which often needed load-bearing inside walls or braces to hold the weight. The gambrel's truss design instead shifted the weight to the outside frame. The top floor could now be used

as a single open space (hence the gambrel's popularity in barns with haylofts), or sectioned up into rooms in any arrangement desired. The nearly vertical angle of the roof also meant that nearly all that inside space was usable, while as much as a third of the interior under a pitched roof was too low to use. The steepness also eliminated worry about snow and ice buildup, and while rain gutters and downspouts were almost unknown in America until the 18th century, the bottom of a gambrel roof often ended in a curvy "kick" overhang to shoot rainwater farther away from the walls and foundation. 1