|

The James Wyatt Oates papers are 20 essays and short stories written between 1879 and 1915. Commentary on selected works can be found in the companion history blog.

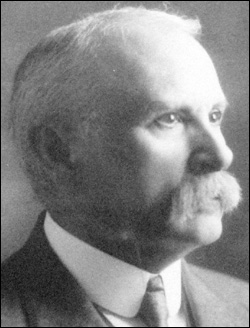

James Wyatt Oates (January 12, 1850 - December 9, 1915) was a writer and prominent attorney in Santa Rosa, California. Today he is best remembered for building what is now known as the 1905 Comstock House, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Called Wyatt by his family, he was the sixth of eight children born to an impoverished farmer in Pike County, Alabama. It was a hardscrabble existence punctuated by acts of violence. The alcoholic father, who had once fractured a man's skull, had a hair-trigger temper that would lead him to beat his children without warning or reason. At age 18, eldest son William fled the state after he mistakenly believed he had killed a man in an argument.1 Oates grew up in the long, intertwined shadows of his brother William C. Oates and the Civil War. William was practicing law when the war began, suspending his practice to organize a company of 121 local men who elected him captain. William would eventually become commander of the 15th Alabama regiment, famous for losing the Battle of Little Round Top at Gettysburg, which is mentioned by historians as a pivotal moment in the Confederacy's defeat. William later became a seven-term Congressman and a one-term governor of Alabama. The year after the war ended, 16 year-old Wyatt killed a man who had insulted his sister. Like William before him, Wyatt fled. He worked in Montreal as a painter for a time, earning enough to pay for college.2 Staying with a relative on the East Coast, he earned a bachelor's degree at Emory & Henry College. He was persuaded by William to return and face trial. Unfortunately, the prosecutor was the father of murdered man, and William had to bribe him a "considerable sum of money" to drop charges because Wyatt would have otherwise been convicted.3 At age 19 James W. Oates was appointed to become a cadet at West Point, during only the second year that residents of formerly Confederate states were eligible to be cadets. He was not admitted, however, because he refused to take the entrance exam, perhaps because there was a question related to felony prosecutions or criminal charges. It was very unusual for a candidate to decline the examination.4 Instead of following William into a military career, Wyatt followed him into the legal profession, passing the bar after studying under his brother's guidance. Together they practiced for several years in their hometown of Abbeville, Alabama. In this period the Southern Law Review published Wyatt's legal analysis, "Homicide and the Defense of Insanity." Here Wyatt made the distinction that it was not so important that judgement should be concerned whether a reasonable man might kill someone under the circumstances, but instead that the accused honestly believed circumstances forced him to commit homicide. (It is hard not to wonder how this argument might be applied to Oates' own act of homicide.) His 1874 analysis was Oates' most significant intellectual work, and can be found cited in law journals over sixty years later. Wyatt suspended his legal career and drifted around Texas, then Arizona, where he again practiced law while editing a "country newspaper."5 In the late 1870s it seems Oates regarded himself primarily as a writer. In a book profiling elected officials, the biography of William Oates did not mention his brother as an attorney but rather "one of the most brilliant and forcible writers on the Pacific Slope."6 Five of the works Oates preserved in his notebook were published during that period. For reasons unknown, Wyatt chose to move to Santa Rosa in 1881.7 He may have heard that the town was notable in California for its sympathies to the Old South and Confederate causes. Oates married Mattie Solomon the following year, registering to vote for the first time in Santa Rosa. He appeared in the city directory for the first time in 1885, listed as a Santa Rosa resident and partner in a law firm. It appears likely that brother William again came to his aid, this time using his connections as a member of Congress. One of Wyatt's law partner was Barclay Henley, who was one of William's fellow Democratic party Congressmen, and the third partner knew the family from Alabama. In 1886 James W. Oates also was awarded the patronage job of Special U.S. Attorney, where he advised the Attorney General whether or not to prosecute timber companies for illegal logging of federal land. In Oates' notebook there is a gap of about two decades where he wrote (or perhaps, kept) little. During that period the newspapers reported he was frequently in San Francisco on legal business and was active in local political and civic affairs, including launch of the Santa Rosa Rose Festival in 1894. Wyatt and Mattie did not have children but had long mentoring relationships with at least two young women in that time, particularly Anna May Bell Dunlap, who was at his bedside as he died. Wyatt maintained close ties with his brother, and William or his family alone traveled to California for lengthy visits. To his associates in California, Wyatt revealed he had fled Alabama after shooting someone in 1866, but in his version of events, the victim survived.8 Oates returned to writing in earnest again in 1910, the year he turned sixty. Both Wyatt and Mattie had been steadily scaling back activities since 1907, and were rarely mentioned in the newspapers any longer. Wyatt followed his brother's example by inviting a young man named Hilliard Comstock to join his office while he read for the bar. Oates developed a fascination with automobiles and was elected president of the Sonoma County Automobile Association. Also in the autumn of 1910, his beloved brother William died. Mattie Oates died in 1914 following years as a semi-invalid and Wyatt had her remains placed in the temporary holding vault at Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery, where she joined her mother who had died in 1910. It was unusual - but not unheard of - for bodies to be stored there for many months or years as a family vault or monument was being prepared. As Wyatt followed William's lead in all things, it is possible he planned for them all to be interred under a glorifying monolith, such as the obelisk with life-size statue that marked William's grave. Oates had already purchased a large plot at the entranceway of the Rural Cemetery. Following his wife's death, Oates visited relatives in Alabama, including William's son, Willie, who was to be heir to almost his entire estate. He also saw Mattie's sister and seemed to develop a rapport with her daughters, bringing them to California when he returned. That winter Oates also invited Hilliard Comstock to move in when his family's ranch flooded. Oates was apparently invigorated by being around young adults; in his obituary it was noted he returned from a visit with Anna May Bell Dunlap and her husband "bubbling over with happiness."9 In the last six weeks of his life, however, Oates reconsidered his legacy. He wrote a codicil to his will that completely disinherited Willie, even denying him the heirloom gold watch that William gave Wyatt on his 21st birthday. Instead, most of the estate went to Mattie's nieces who accompanied him back to California. As an even more extreme gesture Oates ordered his body to be cremated, together with the bodies of Mattie and her mother which had been stored in the cemetery holding vault. He ordered that the remains of Mattie's two sisters and brothers be disinterred along with his father-in-law - a man who Oates could not possibly have known because he died in San Francisco when Oates was a 13 year-old boy in Alabama. All of their bodies were to be cremated together. "The ashes will be thrown to the winds by Dr. Bogle, in conformity with another wish of Colonel Oates," a Santa Rosa newspaper reported. "The cremation of this number of bodies from the same family, all in one day, is a very unusual proceeding."10

NOTES ON SOURCES: The James Wyatt Oates papers were collected in a three-ring binder (presumably by Oates himself) and preserved by the family of Hilliard Comstock, with particular thanks to Martha Comstock Keegan. The works were not organized in chronological order, but were grouped together under alphabetical dividers. This original order is reflected here in the directory name structure. Thus the "Washington Territory" essay, for example, is stored as "a/californian1/washingtonterritory.pdf" which indicates that it was found under the "A" divider and was the first sequential essay from "The Californian." Most of the unpublished works were under the "T" divider and identified here as directories "t1" through "t15." The significance of the order, if any, is unknown. The documents were scanned January 28-29, 2013, using a Fujitsu ScanSnap S1300i with ABBYY FineReader OCR.

|